Increasingly, in our culture, we find ourselves framing our experiences through the lens of psychiatric and mental health concepts. This is particularly noticeable in young people, who, even more than adults, seem to make sense of their identities through this kind of language.

The mental health framework has its use. Concepts from psychology, psychoanalysis, psychiatry, at their best can involve nuanced insights into our thoughts and feelings. But this language goes all the way down to psychobabble, tele-psychology and diagnosis via TikTok and that’s a more complicated picture.

For better or worse, the mental health framework has largely replaced earlier frameworks rooted in mythology and oral traditions, philosophy, religion, politics as well as literature and art, science and even astrology and alchemy. Human communities, at different contexts and times in history, drew on these different traditions seeking knowledge and guidance about existence, meaning, suffering, illness and death, the stages of life, and morality. Today, mental health and its terminology occupy much of that space, in how people refer to themselves and understand their reactions, and how they approach others.

While this framework comes with benefits, it has problems too and the pro-anti diagnosis debate is quite polarised. Much has been said – and I certainly share my own misgivings – about the problems that arise when adolescents struggle to see beyond a set of symptoms and the diagnosis they attribute to themselves.

It makes sense that teenagers opt for this framework, given that it reflects the language of our times. Our entire society is structured around this type of categorisation, and diagnostic, psychiatric and psychological language is rife in the adult world too.

But when and under what conditions is diagnosis useful?

At its best, when a psychological formulation is nuanced and goes to some depth, it offers a reasonable explanatory framework to name and formulate a problem and speak about experience. Some would say that philosophy or even literature can give us even better formulations! But I think that psychology and psychoanalysis can offer really helpful ways, one framework amongst others, for understanding what’s happening with our lives.

Yet, at its worst, when a psychological framework is taken as a ‘magic solution / one size fits all’ approach, it can have unintended consequences, lending itself to generalisations and big jumps to conclusions.

It’s clear that we can’t simply do away with the mental health framework or imagine ourselves completely outside it, as this framework is now so culturally ingrained. The categorisations it proposes are deeply ‘baked into’ our culture. So, the question becomes: how do we navigate the current landscape? How do we open up a dialogue with it? How do we engage with all aspects of the mental health framework, using it … when it’s useful! Thus – without rejecting it outright, and without adopting an either/or position.

What are some of the positives of a diagnosis?

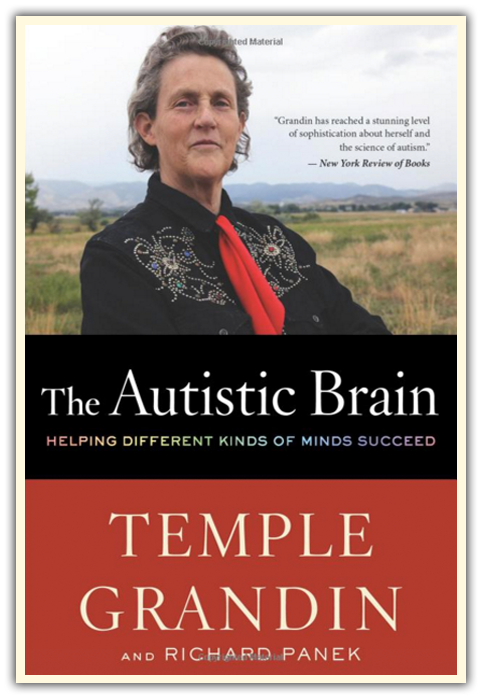

Much has been written and fiercely debated on the challenging question of psychiatric diagnosis – overdiagnosis, underdiagnosis, misdiagnosis, self-diagnosis … One author whose work has helped me think through this maze is Temple Grandin. A well-known academic who herself has an autism diagnosis, Grandin has explored this subject in depth. Her book ‘The autistic brain’ contains a plethora of compelling facts about the autism spectrum. She brings alive both the positives of diagnosis for young people and some of its drawbacks. I’ll let her do the ‘talking’ here through some key points about what she calls ‘label-locked thinking’.

Here’s Temple Grandin’s point of view on why a diagnosis can be helpful:

“I’m not saying that we shouldn’t use labels. Of course we should. Without the label that Leo Kanner gave it, autism might have gone undiagnosed, untreated, and just plain ignored. Labels have been incredibly important, and they will continue to be incredibly important. For the purposes of medicine, educational benefits, insurance reimbursements, social programs, and so on, they’re necessary. And if you’re a researcher looking into autism, sometimes it makes sense to test only autistic subjects against controls. But sometimes it doesn’t, because autism is not a one-size-fits-all diagnosis.”

Several issues come up here: the importance of early identification and intervention to address problems before they escalate; the clinician’s need for a clear formulation to build a treatment plan; and the pragmatic choice to pursue a diagnosis for access to much needed support services. (As an aside, this can become a problem today when the system becomes inundated with too many requests because of the over-emphasis on diagnostic explanations for all sorts of experiences, while at the same time there is very limited funding for this kind of support by councils).

However. (And there are a number of howevers here)…

Temple Grandin says:

“I warn parents, teachers, and therapists to avoid getting locked into the labels. They are not precise. I beg you: Do not allow a child or an adult to become defined by a DSM label”

She repeatedly stresses in her book that a label doesn’t address the issue of what we can do with the suffering experienced, how the young person can be helped: “Don’t worry about the label” she says. “Tell me what the problem is. Let’s talk about the specific symptoms”. She’s right.

She also says:

“Label-locked thinkers want answers. This kind of thinking can do a lot of damage. For some people, a label can become the thing that defines them. It can easily lead to what I call a handicapped mentality’… but: ‘Label-locked thinking goes the other way too. You might be comfortable with your diagnosis but worry that it will define you in the eyes of others.”

My final take-away from her book is her scary but increasingly true observation that sometimes a diagnosis can lead to (paradoxically) less treatment:

“Label-locked thinking can affect treatment. For instance, I heard a doctor say about a kid with gastro-intestinal issues, “Oh, he has autism. That’s the problem” – and then he didn’t treat the GI problem. That’s absurd. Just because gastrointestinal problems are common in people with autism doesn’t mean that the GI problems are untreatable on their own. If you want to help the kid with GI issues, talk about his diet, not his autism.”