A recent LinkedIn post by researcher and social worker Nicholas Marsh made me mull over issues of terminology. What’s the most suitable term for those between 13 and 18? And wider: what’s at stake in how we name developmental periods?

Marsh points out that there’s a longstanding debate amongst professionals on how we should refer to teenagers. There are two sets of arguments. On the one side, it’s claimed that calling teenagers ‘children’ guards against adultification bias, the risk of viewing adolescents, particularly Black adolescents, as older and more adult-like than they are.

There is an important point here. The risk of adultification is most pronounced for adolescent Black girls; research has shown repeatedly that they tend to be viewed and treated, subtly but unmistakenly, as older than they are. The repercussions are far reaching: in school exclusion rates; in how uniform and hair style infringements are treated; in offers of support and nurturing. The net results tends to be an overall risk of harsher punishments.

A straightforward answer to this problem is to focus on language that would (hopefully) work correctively, calling all under 18s children. But that brings its own problems.

The problems with the term ‘child’

The problems with the term ‘child’

Marsh invites us to consider some of the drawbacks. First, using the term ‘child’ strips away the rights adolescents have due to their age, rights which mark them as different to both adults and younger children.

Incidentally, this exact question was discussed during the UK Brexit referendum and the Scottish independence referendum: young people, it was convincingly argued, are the ones who will mostly be impacted by the outcome of the referendums. It follows that they should be allowed to vote. This remains an open debate, with different arrangements in the UK: Scottish and Welsh youth vote from 16, while their English and Northern Irish counterparts cannot, leading to a push towards voting rights extending to younger ages for those areas too. Marsh’s main point is this:

By calling adolescents ‘children’, professionals may unintentionally infantilise them and deny them the agency and autonomy they need to navigate the complexities of adolescence.

He reminds us, also, that in England:

‘legislation and statutory guidance have long used the term ‘child’ to refer to individuals under 18 (Children Act 1989, 2004; Working Together to Safeguard Children). Despite this, young people in England have still faced being adultified and may not have received the care and protection they deserve (see Child Q- Hackney)’.

The point is that the terminology we use is just a small part of the story. Changing words, on its own, doesn’t solve adultification bias. Many other things need to be put in place; as Marsh comments in the dialogue following his post, ‘the onus should be on actions and impact, not only language’.

Even if not everything, language, of course, does matter. Moreover, it’s in permanent flux. When it comes to the ‘messy bit in between childhood and adulthood’, a BBC article reminds us that ‘adolescence’ used to have other names and other meanings in former historical moments. Among terms used, teenagers used to be called …

Younkers. Ephebes. (and even) … Backfisch!

One thing has remained the same though. Adolescence, a physiological, mental, emotional and cognitive process, has evolution and change at the heart of it.

To frame and support this period of change and milestones, all this matters: thow we understand and culturally mark adolescence; what names we use; how society views and treats young people; how they view and think about themselves; how they spend their time; where they go, what they do. All these choices have an impact – sometimes small, sometimes bigger – on what adolescence is today.

For example, in the past the transition between childhood and adulthood had a very different framing. Adolescents were expected to contribute actively to the household and work, with a seamless line between childhood and adulthood.

For example, in the past the transition between childhood and adulthood had a very different framing. Adolescents were expected to contribute actively to the household and work, with a seamless line between childhood and adulthood.

Today, with the much documented delayed, longer growing up process until the mid-20s, childhood for some adolescents is extended until later, risking the diminishment of rebellious, risk-prone, sex drugs and rock ‘n roll adolescence. The pendulum swings both sides, with some adolescents staying in childhood limbo too long, while others entering adult territory far too early.

And what about sexuality?

What seems absent in these terminology debates is sexuality. Amongst all the big changes that happen during the teen years, the emergence of sexuality is surely one of the most profound. But adolescents’ budding sexuality tends to be mentioned in these debates as an afterthought. Or as a negative, something that has to be managed and tamed: the dangers of adultification; the risk of ‘early sexualisation’; spiking, sextortion, assault…

Looking at it through this lens, the push to name adolescents ‘children’ marginalises sexuality. It overlooks what makes adolescence adolescence – namely, the changes in the body and the growth of new ways to see oneself and others.

Sexuality has been marginalised even within the psychoanalytic world

This marginalisation has happened even within psychoanalysis, the field that was born through Freud’s underlining of the prominence of sexuality and its inherently traumatic and unsettling effects, even if all progresses well. In modern psychodynamic schools, there is an increasing emphasis on the early mother-infant bond and a turning away from sexuality. One of the things that psychoanalytic theory taught us is that there is something untameable and messy within sexuality, however much we wish to control or overlook it. But more and more, this idea is put aside.

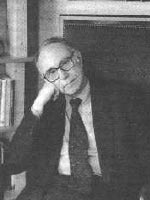

Back in 1995, French psychoanalyst André Green asked: “Has sexuality anything to do with psychoanalysis?” He pointed out that sexuality is increasingly not seen as central in understanding child development, or clinical psychopathology, and shared his observations:

Back in 1995, French psychoanalyst André Green asked: “Has sexuality anything to do with psychoanalysis?” He pointed out that sexuality is increasingly not seen as central in understanding child development, or clinical psychopathology, and shared his observations:

“direct discussion of sexuality seems to have declined in ordinary clinical presentations and sexuality also seems to have become marginalised and restricted to specialised papers in psychoanalytic journals.”

He argued, though, that sexuality is very much part of life, and comes up in clinical discussions:

Our patients still complain about disturbances in their sexual lives with more or less complete impotence, frigidity, lack of satisfaction in sexual life, conflicts related to bisexuality or to the fusion and defusion of sexuality and aggression, to say the least. Changes and present social habits of people have not brought a significant improvement of sexual life in proportion to the modifications of public morals.

Following this line of thought, adolescence, the transitional time between childhood and adulthood, is distinct and deserves terms that incorporate the body and sexuality as central. The term ‘child’ brings in the language of needs and protection; while the bland term ‘young person’ speaks the language of rights and responsibilities. But what make these years distinct are the flux, turmoil and transitionally that all these physical changes and the eruption of sexuality bring. Perhaps the term ‘adolescent’ is good enough to bring all this together.